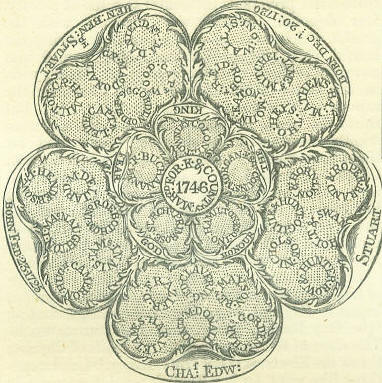

18th AugustBorn: Dr. Henry Hammond, eminent English divine, 1605, Chertsey; Brook Taylor, mathematician, 1685, Edmonton; John, Earl Russell, from 1846 to 1852 Prime Minister of Great Britain, 1792, London. Died: Empress Helena, mother of Constantine, 328, Rome; Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, ministers to the rapacity of Henry VII, executed on Tower Hill, 1510; Pope Paul IV, 1559; Guido Reni, celebrated painter, 1642, Bologna; William Boyd, Earl of Kilmarnock, and Arthur, Lord Balmerino, beheaded for high treason, 1746, London; Francis I, Emperor of Germany, 1765, Innspruck; Dr. Benjamin Kennicott, biblical editor, 1783, Oxford; Dr. James Beattie, poet (The Minstrel), 1803, Aberdeen. Feast Day: St. Agapetus, martyr, about 275. St. Helen, empress, 328. St. Clare of Monte Falco, virgin, 1308. THE REBEL LORDS OF 1746Four of the Scotch nobility, who had joined in the insurrection of 1745, were condemned to death. One, the Earl of Cromarty, was pardoned, very much out of pity for his wife and large family. A second, Lord Lovat, was executed in 1747. The remaining two suffered decapitation on Tower Hill, on the 18th of August 1746, while the country was still tingling with the fear it had sustained from the rising. Of these, the Earl of Kilmarnock, a gentle-natured man of two-and-forty, professed penitence. The other, Lord Balmerino, a bluff old dragoon, met death with cheerful resignation, avowing his zeal for the House of Stuart to the last. The scaffold erected for this execution was immediately in front of a house which still exists, marked as No. 14 Tower Hill. The two lords were in succession led out of this house on to the scaffold, Kilmarnock suffering before Balmerino, in melancholy reference to his higher rank in the peerage. Their mutilated bodies, after being deposited in their respective coffins, are said to have been brought back into the house, and in proof of this, a trail of blood is still visible along the hall and up the first flight of stairs. There is a contemporary print of the execution, representing the scaffold as surrounded by a wide square of dragoons, beyond which are great multitudes of people, many of them seated in wooden galleries. The decapitated lords were all respectfully buried in St. Peter's Chapel within the Tower. There were in all between eighty and ninety men put to death for their concern in the Forty-five. Many of them suffered on Kennington Common, including two English gentlemen, named Francis Townley and George Fletcher, who had joined the prince at Manchester. The heads of these two were fixed at the top of poles, and stuck over Temple Bar, where they remained till 1772, when one of them fell down, and in a storm, the other soon followed. There were people living in London not long ago, who remembered having in their childhood seen these grisly memorials of civil strife. Many readers will remember the jocular remark made by Goldsmith to Johnson, with reference to the rebel heads of Temple Bar. Johnson, who was well known to be of Jacobite inclinations, had just quoted to Goldsmith from Ovid, when among the poets' tombs at Westminister Abbey Forsitan et nostrum nomen miscebitur istis. Passing on their way home under Temple Bar, Goldsmith slily whispered in Johnson's ear, pointing to the heads Forsitan at nostrum nomen miscebitur istis. Previous to the rebellion of 1745, Temple Bar, for about thirty years, exhibited the head of a barrister named Layer, who had been executed for a Jacobite conspiracy, soon after Atterbury's Plot. At length, one stormy night, the head of Layer was tumbled down from its station, and being found in the morning by a gentleman named Pearce, was taken into a neighbouring public-house. It is said to have there been buried in the cellar; nevertheless, a skull was purchased as Layer's by Dr. Rawlinson, an antiquary, and, on his death in 1755, was buried in his right hand. DECLINE AND END OF THE JACOBITE PARTYIt is scarcely necessary to remark that Jacobitism proceeded upon a principle, which is not now in any degree owned by anybody in the United Kingdom-that a certain family had a simply hereditary right to the crown and all the associated benefits, and could not be deprived of it without the same degree of injustice which attends the taking of a man's land, or his goods, or anything else that is his. 'The king shall enjoy his own again!' was the burden of a song of the Commonwealth, which continued in vogue among the Stuart party as long as it existed. Those who made and sang it, had no idea of any right in the many controlling this supposed right of one; and there, of course, lay their great mistake. Granting, however, that the Jacobites viewed the case of the Stuarts as that of a family deprived of a right by unjust means, we must admit that their conduct in trying to effect its restoration was not merely logical, but generous. In the heat of contention, the Revolution party could not so regard it; but we may. We may-while deploring the short-sightedness of their principles-admire their sacrifices and efforts, and pity their sufferings. After the House of Brunswick had been well settled in England, the chance of a restoration of the Stuarts became extremely small. The attempt of 1745, brilliant as it was in some respects, was a thing out of time, a mere temporary and, as it were, impertinent interruption of a state of things quite in a contrary strain. The Jacobites were chiefly country gentlemen-men of the same type who are now known as ultra-conservatives. They were important in their own local circles, but could exercise little influence on the masses. The essential weakness of their cause is shewn in the necessity they were under of putting a mask upon it. A constant correspondence was kept up between them and the Stuarts, but under profound secrecy. Portraits and medals of the royal exiles were continually coming to them, to keep alive their bootless loyalty. An old lady would have the face of James III. so arranged in her bedroom, that it was the first thing she saw on opening her eyes in the morning. The writer has seen a copy of the Bible, with a print of that personage pasted on the inside of the first board. The contemplation of it had been a part of the owner's devotions. There was also a way of shewing the Stuart face by a curious optical device, calculated to screen the possessor from any unpleasant consequences. The face was painted on a piece of canvas, in such a way that no lineament of humanity was visible upon it; but when a polished steel cylinder was erected in the midst, a beautiful portrait of 'the king' or 'the prince' was visible by reflection on the metal surface. There were also occasional presents of peculiar choice articles from the Stuarts to their adherents. A gentleman in Perthshire still possesses the silver collar of an Italian greyhound, which was sent to his grandmother, considerably more than a hundred years ago, the collar being thus inscribed: 'C. STEWARTUS PRINCEPS JUVENTUTIS.' On the other hand, when some ingenious manufacturer produced a ribbon or a garter coloured tartan-wise, and containing allusive inscriptions, initials, or other objects, samples of it would be duly transmitted to the expatriated court. The Jacobites dealt largely in songs metaphorically conveying their sentiments, and some of these, from this very additional necessity of metaphor, are tolerably effective as samples of poetry. Dr. William King, president of St. Mary's Hall, Oxford, and Dr. John Byrom of Manchester, were the chief bards of the party about the middle of the century. The Jacobites also dealt largely in mystically significant toasts. If the old squire, in giving 'The king,' brought his glass across a water jug, it was held to be a very clever way of shewing that he meant 'The king over the water.' If some Will-Wimble-like dependent, on being asked for his toast, proposed, 'The king again,' it was accepted as a dexterous hint at a Restoration. One of Dr. Byrom's toasts was really a clever equivoque: God bless the king-I mean the Faith's Defender. God bless-no harm in blessing-the Pretender. Who that Pretender is, and who that king, God bless us all, is quite another thing. This was set forth in Byrom's works, as 'intended to allay the violence of party-spirit.' One of the hopeful sons of the squire was sure of an additional apple, if he could clearly enunciate to the company at table the following alphabet: As another specimen of their system of equivocation, take the following verses, as given on the fly-leaf of a book which had belonged to a Jacobite partisan: I love with all my heart The Tory party here The Hanoverian part Most hateful doth appear And for their settlement I ever have denied My conscience gives consent To be on James's side Most glorious is the cause To be with such a king To fight for George's laws Will Britain's ruin bring This is my mind and heart In this opinion I Though none should take Resolve to live and die my part To appearance, this was a long poem of short lines, conveying nothing but loyalty to the Hanover family, while, in reality, it was a short poem in long lines, pronouncing zealously for the Stuarts.  Mr. Richard Almack, F. S. A., Melford, exhibited at a recent meeting of the Archeological Institute, a very affecting memorial of the Jacobite party, in the form of an impression from a secretly engraved plate, supposed to have been executed by Sir Robert Strange, and of which a copy is here reproduced on wood. It professedly is a sort of cenotaph of the so-called 'Martyrs for King and Country in 1746.' The form, as will be observed, is that of a full-blown five-petalled rose, on which arc thirty-five small circles, containing each the name of some one who suffered for the cause at the close of the insurrection of 1745-6; as also, on the extremities, those of Prince Charles and Prince Henry Benedict, with the dates of their births. Amongst the names of the sufferers are those of Captain John Hamilton, who had been governor of Carlisle for the Prince, and surrendered it to the Duke of Cumberland, Sir Archibald Primrose, Francis Buchanan of Arnprior, Colonel Townley, who had raised a rebel regiment at Manchester, and Captain David Morgan, originally a barrister. The others were persons of less account; most of them were put to death in barbarous circumstances on Kennington Common. It is rather remarkable that the names of Lords Balmerino and Kilmarnock are not given: it might be because the latter had professed repentance of his rebellion on the scaffold, and there would have been an awkwardness in giving the former alone. Jacobitism may be said to have ceased to have a profession of faith at the death of Charles Edward in 1788. Little of it survived in favour of Cardinal York, who, at the death of his brother, was content to issue a medal bearing his name as 'Henricus Nonus Dei Gratia Rex,' with the meek addition, 'Haud desideriis Hominum, sed voluntate Dei.' The feeling may be said to have merged in an attachment to George III, on his taking so strong a part against the French Revolution and Friends of the People-a position which made him something like a Stuart himself. |