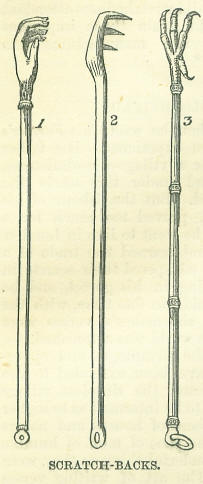

19th AugustBorn: Elizabeth Stuart, Electress-Palatine of the Rhine, queen of Bohemia, daughter of James VI of Scotland, 1596; Gerbrant Vander Eeckhout, painter, 1621, Amsterdam; John Flamsteed, astronomer, 1646, Denby, Derbyshire; Francis I, king of the Two Sicilies, 1777; James Nasmyth, engineer, 1808, Edinburgh. Died: Octavius Caesar Augustus, first Roman emperor, 14 A.D., Nola; Geoffrey Plantagenet, brother of Richard Coeur-de-Lion, killed at Paris, 1186; Blaise Pascal, author of the Provincial Letters, 1662, Paris; John Eudes, priest, founder of the Congregation of Jesus and Mary, 1680, Caen; Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, practical philosopher, 1814, Auteuil; Robert Bloomfield, poet (The Farmer's Boy), 1823, Shefford, Bedfordshire; Sir Martin A. Shee, president of Royal Academy, 1850, Brighton; Honoré de Balzae, French novelist, 1850, Paris. Feast Day: Saints Timothy, Agapius, and Thecla, martyrs, 304. St. Mochteus, bishop and confessor, 535. St. Cumin, bishop in Ireland, 7th century. St. Lewis, bishop of Toulouse, confessor, 1297. ELIZABETH, ELECTRESS PALATINEHappiness such as rarely falls to the lot of crowned heads, might have been the portion of this lovely and interesting woman, had not a foolish ambition of being called a queen blighted in a moment the whole tenor of her life. The eldest child of James VI of Scotland, she was born at the palace of Falkland, and when baptized, had for a sponsor the city of Edinburgh, in the proxies of its provost and baffles, who stoutly held to their right of seeing the princess brought up in the Protestant faith. When her father departed, in 1603, to take possession of the English throne, he left his consort and young family to follow him; and their progress through the counties was marked by festivals and pageants nearly as grand as those which had signalised the king's own progress. After a short stay at Windsor, it was deemed necessary that the little princess should be withdrawn from her father's palace and placed under the superintendence of Lord and Lady Harrington, at Combe Abbey. Very pleasant is the picture of the life led at this lovely spot, where beautiful gardens, aviaries, park, and river, charmed the eyes of those who had been accustomed to the wild, desolate Scottish scenery. Many noble young ladies were sent to share in the education of Elizabeth, which seems to have been admirably conducted by Lord Harrington: a sincere Christian and learned man, he strove to instruct his pupil more thoroughly in life and its duties, than in mere outside show, and but for the lavish expenditure, arising from her generosity, which he could not subdue, we may say that he succeeded well. At the age of fifteen, the young princess was removed to London, and proposals of marriage came from all the countries in Europe. France and Spain drew back, on the ground of religious differences, and at length Frederick V, Elector palatine, was the accepted suitor, who, though snubbed by the queen for his want of a kingly title, was yet the first in rank of the German princes, ruling those wide and fertile Rhenish Provinces which now form so valuable a part of the Prussian dominions. His reception in October 1612 was of a most joyous kind; water-processions, tiltings, masques, and feasts filled up the days, until the sad death of Prince Henry threw the royal family into mourning. He and his sister had always been strongly attached, and his last words were for her. The opportunity was, however, given for her lover to offer his best consolations, and the deep attachment formed at this period was never abated during the many trials of their married life. St. Valentine's Day was appropriately chosen for the marriage-ceremony; the first royal one that had ever been performed according to the liturgy of the Church of England. James's vanity induced him to load himself on this joyous occasion with six hundred thousand pounds worth of jewels, and the bride's white satin dress was embroidered with pearls and gems, and her coronet set in pinnacles of diamonds and pearls. Having taken a sad farewell of her parents, whom she was never to see again, she sailed to Flushing, and proceeded on a sort of triumphal march through Holland and Germany, arriving at her beautiful palace of Heidelberg amidst arches of flowers and hearty welcomes from her subjects. Frederick lifted her over the threshold in his arms, according to old German custom, and introduced her to his mother and relatives in rooms furnished with solid silver. The great tun of wine stood on the terrace, and was twice drunk dry by the scholars, soldiers, and citizens, who dined in the meadows beneath, by the banks of the Neckar. For six years this happy couple reigned in equal prosperity and popularity; three lovely children rejoiced their parents' hearts; when the Bohemians, roused to insurrection by the oppression of the emperor of Germany, offered their crown to Frederick. Very thankful would the Elector have been to decline such a desperate venture as that of matching his strength with the Imperial forces: but Elizabeth urged him on with the question, 'Why he had married a king's daughter, if he dreaded being a king?' The stadtholder, Maurice, was on her side of the question; while the Electress-Dowager supported her son. Maurice one day abruptly asked the Electress-Dowager: 'If there were any green baize to be got in Heidelberg?' 'Yes, surely,' answered she; 'but what for, Maurice?' 'To make a fool's cap for him who might be a king and will not!' was the reply of Maurice. Thus overcome, Frederick signed the acceptance of the ancient crown of Bohemia, and in October he and his family made a ceremonial entry into the old city of Prague, where Taborites, Hussites, Lutherans, and Catholics were soon at daggers-drawing with each other and their chosen sovereign. The Spanish army immediately seized on Heidelberg and the Palatinate, whilst the Duke of Bavaria's cannon boomed over the Weissenberg, and his soldiers descended on Prague. The unfortunate king assisted his wife into the carriage in which she had to fly for her life, saying: 'Now I know what I am. We princes seldom hear the truth until we are taught it by adversity.' The Catholics broke out into songs of exultation. Mr. Floyd, a member of parliament in England, was expelled from the House, branded, and flogged, for repeating a squib, 'that the king's daughter fled from Prague like an Irish beggar-woman with her babe at her back.' Placards were fixed on the walls of Brussels, offering a reward for 'a king run-away a few days since, of adolescent age, sanguine colour, middle height, a cast in one of his eyes, no moustache, only down on his lip, not badly disposed when a stolen kingdom did not lie in his way-his name, Frederick.' Henceforth this royal pair, with their large family of little princes and princesses, were only indebted to charity for a home. By the kindness of the States-General, Elizabeth found refuge at the Hague. She maintained a brave heart, indulged in her favourite sport of hunting, and seemed to suffer little from the difficulties and privations incidental to a life of penury. Her dejected husband was generally with the armies which were desolating Germany during the fearful Thirty Years' War, until death carried him away in 1632, at a distance from his loving wife, in the castle of Mentz. Sorrow at witnessing the miseries of his people broke his heart when but thirty-six years of age. The sail tidings were wholly unexpected by his poor widow, and for three days she was unable to speak; her brother, Charles I, shewed her great sympathy and kindness, allowing her £20,000 a year, and begging her to come to him. This she declined; but her two elder sons, Prince Charles and Rupert, spent much time at the English court, until the former was once more settled in a part of the Palatinate. Elizabeth occupied herself with the education of her daughters and younger sons, until the troubles began in England, when two of her sons, including 'the fiery Rupert,' joined their unfortunate uncle. The close of the struggle with the death of Charles, threw the Electress at once into deep grief, and something like want, for her English pension necessarily ceased. Her court, nevertheless, became a refuge for the persecuted loyalists, whilst her kind, affectionate temper, made her friends among all sects and parties. Louisa, one of her daughters, skewed such talent for painting, that her pictures were often disposed of to assist the needy household; this clever woman afterwards became a nun at Chaillot, much to her mother's sorrow. The restoration in 1660, brought a last ray of hope to the sorrowful life of Elizabeth. She longed to see her native country once more; and when her nephew, the king, declared his inability to bear the expense of a state-visit, she determined to come incognito, to her generous friend, Lord Craven, who offered her his house in Drury Lane. We soon hear of her entering into the gaieties of London, and being the first lady of the court; £12,000 a year was settled upon her, and happiness seemed in store; but in less than a year after her arrival, inflammation of the lungs attacked her, and she died on the eve of St. Valentine's Day, just forty-nine years after she had been made a happy bride, and was buried at Westminster Abbey, with a torchlight procession on the Thames. Of her seven sons, not one left a grandson; and it was through her youngest daughter, Sophia, that the present royal family came to the British throne. COUNT RUMFORDSir Benjamin Thompson, better known as Count Rumford, was one of those few but fortunate men who have both the means and the inclination to be useful to society generally. He was continually doing something or other, that had for its object, or one of its objects, public or individual improvement. He was an American, born at Rumford, in New England, in 1752. After receiving a good education, and marrying advantageously, he espoused the cause of the mother-country against the colonies during the American war, and was knighted by George III for his services. Sir Benjamin, in 1784, made a continental tour, and eventually entered the service of the king of Bavaria, in the singular capacity of a general reformer. He remodelled the whole military system of the country; he suppressed a most pernicious system of mendicancy that prevailed in Munich; he taught the people to like and to cultivate potatoes, against which they had before had a prejudice; he organised a plan for employing the poor in useful pursuits; and he introduced a multitude of new and curious contrivances of various kinds. He was made a count for his services. He returned to England in 1799, but lived mostly in France, till his death on the 19th of August 1814. Count Rumford's papers in the Philosophical Transactions, and his detached scientific essays, range over the subjects of food, cooking, fuel, fireplaces, ventilation, smoky chimneys, sources of heat, conduction of heat, warm baths, uses of steam, artificial illumination, portable lamps, sources of light, broad-wheeled carriages, &c. He was well-versed in English, French, German, Spanish, and Italian. He founded the 'Rumford Medal' of the Royal Society: leaving £1000 stock in the three per cents, the interest of which is applied biennially, in payment for a gold medal, to reward the best discoverers in light and heat; and he benefited many other scientific institutions. Count Rumford adopted a singular winter-dress while at Paris-white from head to foot. This he did in obedience to the ascertained fact, that the natural heat of the body radiates and wastes less quickly through light than dark-coloured substances. But the most remarkable achievement of Rumford's life, perhaps, was the suppression of the beggars at Munich. Mendicancy had risen to a deplorable evil, sapping the industrial progress of the people, and leading to idleness, robbery, and the most shameless debauchery. The civil power could not battle against the evil; but Rumford took it in hand. He caused a large building to be constructed, and filled it with useful implements of trade-but without letting the beggars into the secret. Having instructed the garrison and the magistrates in the parts they were to fill, he fixed on the 1st of January 1790, as the day for a coup dètat, when the beggars would be more than usually on the look-out for New-year's gifts. 'Count Rumford began by arresting the first beggar he met with his own hand. No sooner had their commander set the example, than the officers and soldiers cleared the streets with equal promptitude and success, but at the same time with all imaginable good-nature; so that before night, not a single beggar was to be seen in the whole metropolis. As fast as they were arrested, they were conducted to the town-hall, where their names were inscribed, and they were then dismissed with directions to repair the next day to the new workhouse provided for them, where they would find employment, and a sufficiency of wholesome food. By persevering in this plan, and by the establishment of the most excellent practical regulations, the count so far overcame prejudice, habit, and attachment, that these heretofore miserable objects began to cherish the idea of independence-to feel a pride in obtaining an honest livelihood-to prefer industry to idleness, and decency to filth, rags, and the squalid wretchedness attendant on beggary. In order to attain these important objects, he introduced new manufactures into the electoral dominions.' ROBERT BLOOMFIELDRobert Bloomfield, when he wrote his Farmer's Boy, drew upon his own experience. His father was a tailor, his mother a village-schoolmistress, his uncle a farmer, and under this uncle the fatherless lad was placed. But the labour of his employment, it is said, proved too much for a delicate constitution; so he went to live in London with an elder brother, and learned the trade of a shoemaker. The Muses whispered their secrets in his ear, as he sat working in his garret, and he wrote down what they said: in due time, with the help of a patron, the shoemaker's verses were published, and the polite world was astonished. In these days, when the advantages and opportunities of education have been extended to the humblest in the land, and the simplest village letter-carrier is expected to be informed as to higher matters than mere numbers of houses and names of streets, poems from the pens of men of humble origin are not such a wonderful thing as they were in Bloomfield's time. The art of writing verses is as simple to acquire as the art of mending shoes. Further than this, all men, from whatever classes they may have sprung, and how differently soever they may have been reared to manhood, have inherently the same passions, hopes, feelings, and tendencies. The sweet influences of nature sway the farmer's boy and the lord's heir alike, if in different degrees, or after different fashions. The difficulty which stands in the way of a rustic, when he takes a pen in his hand, is not how to find thoughts, or feel emotions, but how to give expression to them. This difficulty education has tended much to remove, and hence we now encounter poetic post-boys and rhyming shoemakers much more often than we used to do. Poor Robert Bloomfield! Ambition led him astray! He was lifted off his feet. When the great smiled on him, he thought himself famous; when they forgot him in due course, he sickened and despaired, and only preserved his reason by surrendering his life. It is a sad thing not to distinguish clearly what one is, and what one is not, and a most dangerous thing for one who is deserving to hanker after notoriety. THE SCRATCH-BACKThe curious little instruments here figured are of extreme rarity, and probably not many of our readers have ever heard of, much less seen, any examples of them. The name, 'Scratch-back,' is not very euphonious, but it is remarkably expressive, and conveys a correct notion of the use of the curious little instrument to which it belongs. The 'scratch-back' was literally, as its name implies, formed for the purpose of scratching the backs of our fair and stately great and great-great-grand-mothers, and their ancestresses from the time of Queen Elizabeth; and very choicely set and carved some of them assuredly were. Sometimes the handles were of silver elegantly chased, and we have seen one example where a ring on the finger of the hand was set with brilliants. But few of these relics have passed down to our times, and even in instances where they are preserved, their original use has been for-gotten. At one time, scratch-backs were al-most as indispensable an accompaniment to a lady of quality as her fan and her patch-box. They were kept in her toilet, and carried with her even to her box at the play.  The first one, engraved on the accompanying illustration, is twelve inches in length. At the upper end is an ivory knob, with a hole, through which a cord could be passed for suspension to the waist, or for hanging in the dressing-room. The handle or shaft is mottled, and the practical end, or scratcher, is a beautifully carved hand of ivory. The fingers are placed in the proper position for the operation, and would lead one to believe that the carver must have studied pretty closely from nature. The finger-nails are particularly sharp and well formed, and designed to scratch in the most approved fashion. This seems to have been the most favourite form for this strange instrument, of which form I have seen three examples. The second example in our engraving is of about the same length as the one just described. This instrument is made entirely of horn, one end being pierced for suspension, and the other formed into three teeth or claws, sharp at the ends and bent forward. It is particularly simple in construction, but evidently would be as effective as the more artistic and elaborate example just described. The third specimen which I give is, like the first, partly of ivory, and beautifully carved. The stick or shaft is of tortoise-shell, and it has a little silver ring at the top, and a rim of silver to cover the junction of the tortoise-shell and ivory. The scratcher is formed like the foot of a bird, with the claws set, and, of course, made very sharp at the points. The foot is beautifully carved, and remarkably well formed; and the instrument must have been one of the best of its class. On the under-side of the foot of this example are the initials of its fair owner, A. W., cut into the ivory. It would add to the interest of this little notice could we tell our readers to whom these precious little relics had belonged, and whose fair backs they had scratched; but this we cannot do. All we can do is, to give them representations of these curious instruments, explain their uses, describe their construction, and heartily congratulate our fair friends on their not being required in our day. In former times, when personal cleanliness was not considered essential, when the style of dress worn was anything but conducive to comfort and ease-for it must be remembered that, in the last century, ladies' immensely-high head-dresses, when once fixed, were frequently not disturbed or altered for a month, and not until they had become almost intolerable to the wearer and to her friends-and when the domestic manners of the aristocracy, as well as others, were not of the most refined and delicate kind, the use of these little instruments, with many other matters which we may yet take the opportunity of describing, became almost essential. In our day they are not so, and we have no fear of seeing their use revived. L. L. J. |